Linux Desktop Renaissance

Published 2026-01-12

In the late 1990s into the aughts, the Linux desktop entered a golden era where it really seemed like it might mirror Linux's domination of the server market. Instead, it entered a kind of Dark Age where innovation and adoption somewhat plateaued. Over the last five years or so, there has been a kind of Renaissance in innovation on the Linux desktop that could very well silence that "year of the Linux desktop" joke that started at the end of the Golden Era. To get there though, enough of the existing Linux community must be willing to shake off the dust from years of stagnation, and embrace the kind of innovation that launched the Golden Era of Linux.

In this post I will explain my views on the causes and attributes of the Golden Era, the Dark Ages, and the Renaissance, and the kind of changes we may need to see in the community to see this Renaissance succeed. If you are mostly curious about my thoughts on recent innovations and less interested in my assessments of how we got here, feel free to skip straight to the Renaissance and What's Next sections.

My Personal History

In 1998, I installed Linux (Red Hat 5.1) on my desktop computer for the first time. As a young computer science student learning C and C++, the ability to use low-level command-line tools and view and modify the source of the software powering my desktop was incredible, and empowering. While this started as a dual-boot install, Linux quickly became my default desktop. I'll spare you the Linux greybeard nostalgia over X11 configs, obscure window managers, installing Linux over PLIP, and distro hopping.

A screenshot from my Linux desktop in September 2002, featuring Unreal Tournament, XMMS, IRC, Licq and the Galeon web browser

Linux remained as my personal desktop OS for the next 25 years. During that time I wrote a dozen books and a decade's worth of Linux Journal articles using VIM, self-hosted all of my important services on Linux servers, and gave numerous conference talks on how to use Linux as a desktop and server. Finally, I spent 5 years of my career directly promoting free software full-time as Chief Security Officer and later on as President of Purism, a company that sells laptops and a phone that ships with a fully free-software Linux OS, PureOS, based on Debian.

The Golden Era

I consider the Golden Era of the Linux desktop to have started some time in the later 1990s, and peaked some time in the late aughts. This was an era defined by rapid innovation in Linux in general, coinciding with the dotcom boom and bust, that led to rapid adoption of Linux both as a server and as a desktop. Linux went on to absolutely dominate the server market, and there was a time when it seemed like the desktop was going to follow suit, only to fade in adoption.

There were a number of innovations in Linux in the mid-to-late 1990s that led to folks like me picking it both as their primary desktop and a server. These innovations were willing to reconsider "the ways things have been done" on UNIX platforms, in particular Solaris, and encouraged experimentation and the development of new tools and approaches. A few innovations that were most relevant to the Golden Era (especially on the desktop) were: distributions, package management, and APT. Linux's domination of the server market was the final, key piece that set the stage for Linux becoming a increasingly adopted desktop OS.

Distributions

A distribution (often shortened as "distro") is a curated set of Linux software, along with an installer and other tools that make it easier to install and maintain Linux on a computer. Before Yggdrasil (widely considered the first distro), if you wanted to use Linux you had to go through a labor-intensive process of bootstrapping the whole thing with an initial Linux kernel, then installing a base set of GNU utilities so you could painstakingly copy, compile and install the rest of the software you needed for your system. By the way this is something you can still experience if you want from projects like Linux From Scratch.

Distributions gave people who were completely new to Linux the ability to try it out without having to be an expert in the C programming language or UNIX, an understanding of GNU tools, or an awareness of the rapidly-growing list of Linux software the community had been developing since the early 1990s. This expansion was key to move past a user base that was primarily focused on Linux software development to something closer to mainstream. Distributions started focusing on particular Linux use cases (like desktops, software development, and servers). They then developed installation tools that walked you through the process of selecting a use case to get their pre-compiled, curated set of tools.

Ease of installation was important, because there weren't consumer PC vendors selling computers with Linux pre-installed. If you wanted to use Linux, you would need to install it over the top of (or alongside of) Windows. While initial Linux installers were pretty complicated and required quite a bit of preexisting Linux knowledge, this started to change in the early aughts with innovations from distributions like Corel Linux. While people continued to focus on making the Linux installation process easier, by the early aughts it was already far simpler (and faster) for a novice than reinstalling Windows. Windows didn't dominate the desktop in the aughts because it was easier to install, but because it was pre-installed and supported by the vendor, and worked with hardware out of the box.

Canonical saw the advantages and innovations in the Debian platform, but realized the default installation and overall desktop experience on Debian was still too rough to expand into the mainstream. With Ubuntu, Canonical smoothed Debian's rough edges and helped the Linux desktop enter the golden age with a consumer desktop focus that expanded on Red Hat's enterprise desktop focus. This aimed not just at ease of installation, but the needs of mainstream consumers--enthusiasts that wanted hardware and software to "just work" without a lot of tweaking. Features we take for granted today, like automounting USB drives, laptop suspend, and sound and video working out of the box came from this focus on the consumer desktop.

Distributions became such a critical entry point into Linux with their opinionated curation of and development of tools, and unique approaches to setting up Linux, that they are still a key part of many people's identities. While people may say "I use Linux" they are more likely to say "I use Red Hat / Debian / Ubuntu / Arch / etc.". Indeed one of the climaxes in the dotcom-era documentary Revolution OS, was the IPO of Red Hat--a Linux distribution that established a business model for commercial Linux to follow into the Golden Era.

Package Management

The second key innovation beyond having a distribution to curate and install your Linux system, was a package manager to make it easy to install and update your software. Instead of downloading and compiling all of your software from scratch, distributions pre-compiled software and packaged the binaries into tarballs (Slackware), RPMs (Red Hat, SuSE), or Debs (Debian, Ubuntu). This not only made installation faster, it avoided having to install and manage all of the build dependencies software needed to compile. This allowed Linux users to add software to their system in much the same way they were used to on other platforms: download a package (or multiple packages), use some tool to install them, and then use the software.

Packages also made support and upgrades easier. Software often depends on system libraries that the distribution maintains, and with software in packages, distributions could more easily test that a new version of software would work with the libraries on a system and only introduce breaking changes as part of major releases.

Library compatibility was important. Disk space was at a premium all throughout the Golden Era, so most software depended upon libraries that were shared with the rest of the system. If you wanted your software to run on, say, Red Hat 5.2, you needed to ensure that it was compatible with the versions of the system libraries (such as glibc) in that distribution. As libraries and software updated over time, any incompatibilities that may come up had to be tracked and managed in package updates. Managing and resolving library incompatibilities between different software projects became one of the major values that distributions provided.

APT

The final innovation I want to call out, that I think directly led to the Golden Era of the Linux desktop was APT, a package management tool created by the Debian distribution that solved a critical problem that was as yet unsolved by package managers: dependency management. In the early days of package managers, if you wanted to install a piece of software, it wasn't enough to install its package using the package management tool. Each package typically depended on other packages (system libraries among other things) to function, and if they weren't already installed you needed to track down and install all of those packages first, before your package would install.

APT's innovation was in automating the process of detecting and pre-installing all of the dependencies a package might have, and pulling all of the software down from Debian's package repository. This innovation shouldn't be understated. Before APT, installing software in the 1990s required a lot of research and often trial and error. If you wanted to install software on Windows, Mac, or Linux, you would have to track down the website that hosted that software, download the files from that site, and run your local software installation tool and hope that the packages from that site were compatible with your OS (often they weren't). Decades before "App Stores" adopted APT's approach, APT brought the software (and all its dependencies) to you, with the confidence that if APT installed it, it would be compatible with your system.

Beyond ease of installation, APT also made upgrading all of your software much simpler. Instead of seeking out updates on a per-software basis, APT allowed you to update all of the software on your system with a single tool. Other major distributions like Red Hat and SuSE adopted this approach to their own tools, and as a result the Linux desktop could point to a specific innovation where they were far advanced compared to Windows and Mac.

Server Domination

The single most important factor that led to Linux's golden era on the desktop was its domination of the Internet server market during the dotcom bust. Some may assume Linux took this marketshare from Windows, but even though Microsoft had aspirations to own the Internet market, they only dominated local office infrastructure (local file, print and email servers) and only grudgingly adopted what became de facto Internet standards like TCP/IP. Commercial UNIXes like Solaris were the major players hosting most of the early Internet, and Linux's eventual domination of that market merely prevented Windows from getting a strong foothold.

Solaris was Linux's real competition in an era when companies couldn't install web servers in data centers fast enough. The Open Source community's innovative spirit, especially when it came to improving traditional UNIX tools to make them more featureful and easier to use, contrasted sharply with Solaris, where the priority was stability and backwards compatibility. Indeed early Open Source adoption happened not just on Linux, but on Solaris as sysadmin installed GNU tools to replace proprietary Solaris counterparts, and get more modern versions of tar and other userspace tools, plus the GNU compiler, Emacs, and modern shells like bash.

What unseated commercial UNIXes like Solaris was this ability to rapidly innovate, embrace new technologies, and most importantly, the creation of the free, Open Source Apache web server, combined with Linux's low (or free) cost and its ability to run on inexpensive, commodity x86 hardware. This became especially important after the dotcom bust when venture capital was no longer flowing as freely. As cool as hot-swappable CPUs and RAM were, it was harder for companies to justify $100k+ Sun hardware when they could get good-enough redundancy and reliability out of a handful of commodity x86 servers running Linux.

Apache's domination of the web server market led to what ultimately became known as the "LAMP stack" or Linux (OS), Apache (web server), MySQL (database) and Perl (later PHP, serving the dynamic application "middleware" layer). Sysadmin who were building infrastructure for companies in the aughts no longer had to argue for Open Source in the datacenter. By the mid-aughts it had proven itself as being a reliable alternative to offerings from Sun and Oracle, with commercial support from companies like Red Hat, SuSE and Canonical.

Desktop Adoption and Innovation

The widespread adoption of the LAMP stack meant that many companies were paying full-time employees to develop software for Linux. It was a natural next step for many of these developers and sysadmin to choose the Linux desktop as the ideal platform to develop and test software that was ultimately going to run on Linux servers. Open Source companies, like Red Hat, SuSE and Canonical, were investing engineering time not just on improving the server platform, but also on the enterprise desktop.

Having an influx of software developers who were trying the Linux desktop, not because they were indoctrinated into Open Source philosophies, but because it helped with their full-time job, meant these developers would hit rough edges or bugs in these desktop environments, and some percentage of them joined Open Source communities to improve desktop software, or provide innovations of their own. This growth in users outside of the traditional community was key to advancing the desktop, as it not only provided extra help to the community, it provided new perspectives that drove innovation.

The golden era started with heavy experimentation in desktop UI. While there were certainly efforts to replicate the Windows UI, most of early innovation and experimentation took design cues less from Windows or CDE (Solaris's desktop), but from alternatives like NextStep (Afterstep, Window Maker) or completely different approaches (Fluxbox, Enlightenment). These window managers experimented not just with where window icons might sit on the window itself, but with features like window memory (remembering where windows were and placing them in the same location), tiling, docks to launch applications, multiple desktops, and many other novel approaches.

While KDE and Gnome became the most popular desktop environments, they were both informed by this early period of heavy experimentation. While they each approach the desktop from a different point of view, those points are view were a combination of approaches from non-Linux desktops like Windows, CDE, MacOS 9, NextSTEP (which inspired OSX), and OSX, with the custom innovations from all of the window managers that preceded them. The golden era of the Linux desktop was defined by this tension between an "intuitive" interface (which meant similar to some non-Linux desktop, usually Windows), and improving the user experience with innovations outside of the mainstream.

Another factor that marked this golden era on the desktop was rapid innovation in graphical tools. As people moved to Linux from other platforms, they needed alternatives to proprietary desktop software that wasn't ported to the platform. While many of the graphical desktop tools were Linux-only, often these Open Source tools, like GIMP, VLC, Firefox, and OpenOffice were cross-platform and provided an easy on-ramp to folks curious about Open Source software.

Cross-platform compatibility was another highlight of this era. Tools had to support proprietary file formats and proprietary network protocols. This led to desktop tools that sometimes were more capable than their proprietary counterparts, with chat tools that could communicate with multiple chat networks, and office tools that had much wider document compatibility. A friend of my quipped at the time: "Open Office's compatibility with Word is at least as good as Word's compatibility with [older versions of] Word."

The Dark Ages

In general, what marked the golden era was overall excitement and growth in Linux desktop users, users who were themselves making active contributions to those tools as daily drivers. Each year promised to be "the year of the Linux desktop" yet it wouldn't be long until that enthusiasm started to wane, and "the year of the Linux desktop" became a running gag. Linux desktop adoption stopped growing, stagnated, and ultimately declined. With it, the desktop itself entered a kind of Dark Ages where it continued to progress in a limited way, but that initial spark and enthusiasm was definitely gone. What happened?

In a word: OSX. The release of Mac OSX in 2001 marked a turning point for both the Linux and Mac desktops. OSX combined a UNIX (Mach) kernel and command line environment with a polished UI patterned after NextStep. Apple's tight integration between hardware and software and focus on polish provided a nicer overall desktop experience because all of the hardware features (suspend, volume keys, WiFi, audio and video) worked out of the box. Where Macs had always attracted professional designers, the fact that it had UNIX under the hood started to attract more professional software developers, especially later in the aughts. It wasn't long before Linux had themes that closely imitated OSX's look and feel, but it was window dressing and not the main reason developers were moving to OSX.

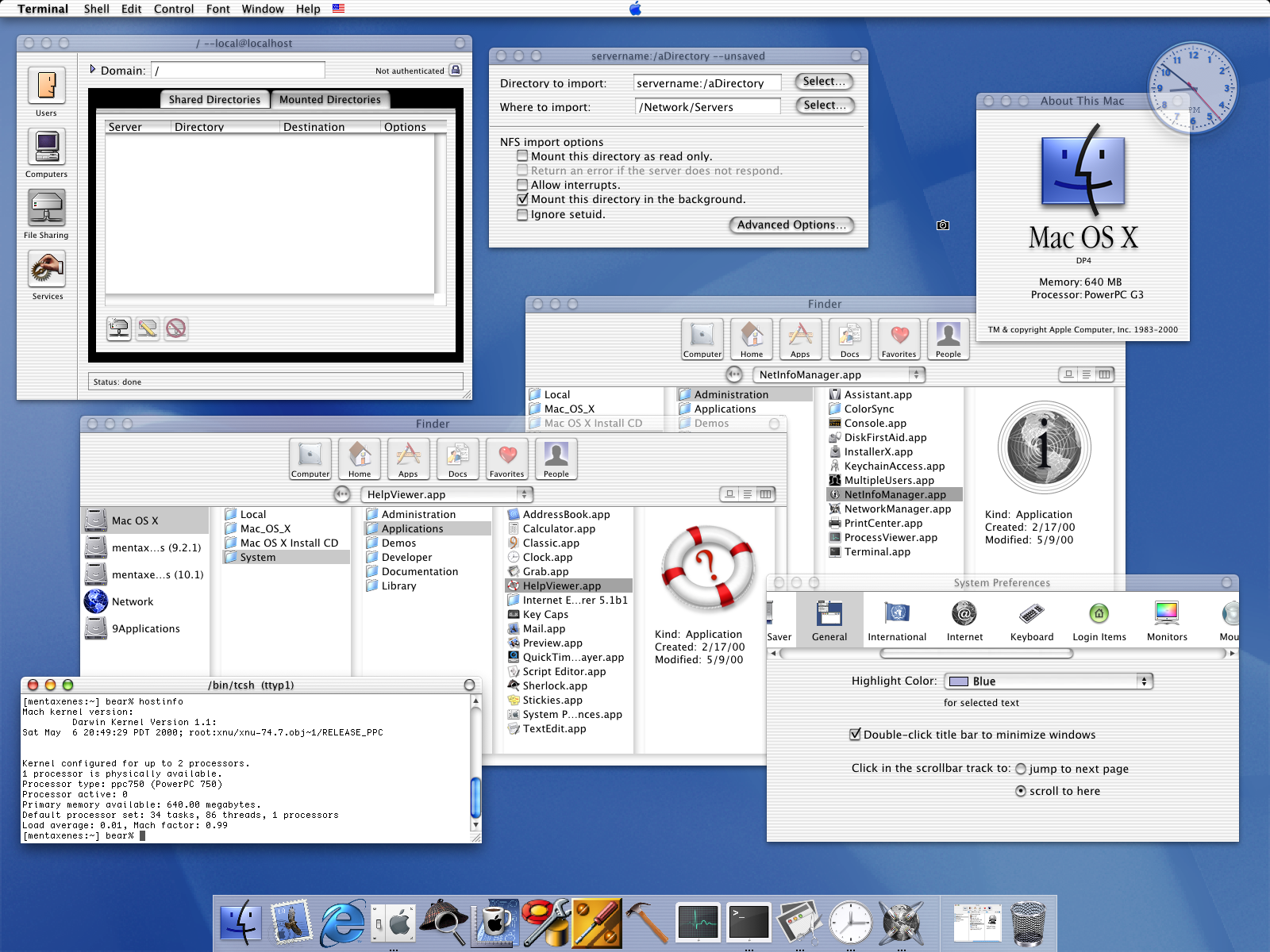

An example screenshot from an early OSX install. Note the Terminal running tcsh, NFS support and translucent effects.

Challenges with Linux Hardware

While Linux hardware support had continued to improve into the late aughts, full hardware support under Linux was rare since kernel developers were often playing catch up to rapidly-changing PC hardware drivers. Even with all the advances during the Golden Era, while Linux could be installed on a majority of PC hardware by this point, most Linux desktop users still didn't have fully-supported hardware after an install. It would take most users hours of research, low-level tweaking, and command line magic to get close to full support of their hardware. Even then a bad resume, or an unlucky software update could lead to something breaking at any time.

The momentum from the Golden Era meant there were many people working to address these rough edges and continue to court the professional Linux developer market. For instance efforts like Dell's "Project Sputnik" (announced in 2012) offered a developer-focused laptop with Linux pre-installed and supported. These were the right approaches, but unfortunately for the Linux desktop, probably too little and too late. The appeal of a polished OSX desktop with hardware and software that "just worked" out of the box was too great for many professional Linux developers to ignore.

Developers Build Linux Tools for OSX

While the Linux desktop worked to smooth its rough edges, the developers who moved to OSX in the mid-aughts started building tools to make their polished desktop productive for Linux webapp development. Homebrew (first released in 2009) allowed developers users an easy way to download and install Linux libraries and software on their Macs. Docker (first released in 2013) allowed developers to package their Linux applications and dependencies inside containers, and solved a common problem developers writing Linux applications on a Mac would encounter: Linux apps that worked on their Mac using tools from Homebrew would break when they moved to actual Linux servers.

By the mid-2010s, it was increasingly common to see Macbooks throughout corporate offices in Silicon Valley startups that a decade before were full of Thinkpads and Dells. The strong demand for developers to build webapps on the cloud meant satisfying their demands, and many demanded a Mac. Like it or not, enterprise IT had to figure out how to accomodate the platform and make it work with their enterprise tools. Macbooks also became common at professional Linux conferences where developers who weren't motivated or constrained by ideology saw no issue or contradiction with using a proprietary desktop to develop an Open Source application if it was the best tool for the job.

Linux Lost the Desktop, but Dominated the Cloud

The irony is that at the same time that Linux was losing momentum on the desktop, it was dominating the server market, now represented by cloud platforms like Amazon's AWS and Google's GCP, and later Microsoft's Azure. By the mid-2010's most companies were in some phase of moving to the cloud, and tech startups in Silicon Valley were largely working on webapps that ran in the cloud on Linux. This domination was so strong that it even forced Microsoft to change its decades-long opposition to Linux and ultimately embrace it on Azure. Microsoft found it hard to convince companies (who had a majority of their cloud platform on Linux in AWS or GCP) to migrate to Windows on Azure.

Stagnation on the Desktop

The loss of professional Linux developers to OSX meant a lot of developer attention went to improving Open Source tools on OSX instead of Linux. Plenty of Linux desktop users remained and continued their work, but the momentum was lost. The Dark Ages were marked by less innovation on the desktop even as Linux server tools continued to advance. Many who stayed on the Linux desktop were long-time users from the traditional Linux community.

That's not to say that there weren't innovations during this period. The Dark Ages saw the creation of systemd as an alternative to System V init, and the creation of Wayland to replace XOrg. A new distribution, Arch Linux, created a new packaging format and among the best repositories of Linux documentation on the Internet. Tiling window managers experimented with desktop UI.

Many of these innovations were (and continue to be) incredibly controversial, because the Linux community by this point was dominated by long-time users motivated by inertia, ideology and tribalism. Linux during this period had a lot in common with Solaris two decades before--an established userbase who had already climbed their learning curve and had tweaked and tuned their environments to suit themselves. These users were resistant to anything that might upset that careful tailoring and require them to learn anything new.

This community was not just resistant to new approaches, but new members, especially anyone resistant to the status quo. Attention turned inward. After years of Linux desktop papercuts, many in the community had built up callouses and could no longer feel them. Many had used Linux so long they had become unaware of (and dismissive of) experiences outside of Linux. There was less interest in smoothing rough edges and adding the kind of polish found on MacOS or mobile platforms. When new users would join the community and complain about these rough edges, they were often dismissed, or told to use a different distro or go back to their old OS.

New software developers from other platforms (especially the growing ranks of mobile app developers) who wanted to develop desktop apps for Linux found this environment challenging. Compatibility with Linux actually meant compatibility with distros and the system libraries they shipped now and into the future. Developers willing to put in the work would typically end up creating a RPM for Red Hat and Fedora, a Deb for Debian and Ubuntu, and some sort of generic tarball to satisfy everyone else. Mobile-first developers (like Signal) would end up using webapp technologies like React or some other framework.

Ultimately the Dark Ages are identified by a Linux desktop that stayed mostly the same throughout, quirks, rough edges and all. A Linux developer who moved to OSX during the end of the Golden Age, could install Linux on their desktop a decade later and find the overall experience largely unchanged. To many in the community, this is considered a feature.

The Renaissance

While it's hard to assign strict dates to any of these ages, the characteristics that define what I think of as the Linux desktop Renaissance started taking hold in the early 2020s. Not everyone who used Linux during the Dark Ages was satisfied with the status quo. While the Linux desktop stagnated, the server environment continued rapid innovation and created technologies focused on containers and continuous deployment in a world where cloud deployment was the default ("cloud native"). A Linux desktop user who entered a time machine in 2010 and exited in 2020 would find life largely the same. A Linux server administrator on the other hand, would barely be able to recognize their job as they ramp up on Docker, Terraform and Kubernetes.

It's this attempt to adapt some of the most successful cloud native innovations to solve similar problems on the Linux desktop that most defines the current Renaissance. Those leading this Renaissance aren't primarily outsiders, more often than not they are Linux experts who work on cloud technologies professionally and realized that the same technologies and patterns that have solved their server problems could solve their desktop problems.

Many of the problems cloud native technologies faced and then solved on servers were ironically consequences from some of the same innovations that led to Linux's Golden Age on the desktop and server. Solving these problems has meant sidelining, replacing, or even erasing these innovations with something new.

Moving Past Distributions

In the cloud, distributions became less and less important until ultimately they ended getting in the way. In an environment where servers were spun up and down dynamically, you no longer have time for installers to walk you through installing your OS and software. Instead, you depend on small, pre-built images with a base OS that can load your custom software. New distro-agnostic tools like Puppet, Chef, Ansible and Terraform focused on automating the process of deploying software and configurations to these base images and cloud environments completely sidestepping distro installation tools.

Moving Past Package Management

As Linux application development moved to OSX, Docker created a new way to package software that removed a lot of the challenges with matching your development libraries with system libraries on the server OS. In a world where software was shipped in containers, the distro it ultimately ran on, and nuances of its package management, stopped mattering as much. Instead, ensuring containers were as small as possible became the focus and administrators focused on distributions like Alpine that provided minimal base OS images to build containers on top of.

Containers meant developers could focus on their software, and no longer had to research how to package software for different distributions, or what system libraries they used. They didn't have to depend on that community of volunteers to package software updates for them. Instead, developers relied on their own CI/CD (continuous integration / continuous deployment) scripts they used to build and test software on their desktop to take a minimal base image and build their software along with the particular libraries and supporting tools their software needed. The resulting container was a distro-agnostic artifact. As long as the downstream platform could run containers, it didn't matter as much what version its OS was, or whether it was Debian, Red Hat, a Kubernetes cluster, or a container service on the cloud.

Removing distro package management from the equation made upgrades easier, as developers no longer had to worry that upgrading their software's libraries would result in incompatibilities with a distro's system libraries. The underlying system was separate from the userspace software that ran on it. Because containers were self-contained by design, there was less worry that the software would behave differently on different servers.

Containers on the Desktop

If it wasn't already obvious, the Linux desktop has suffered from the same problems as the cloud. There has been a longstanding tension, best represented by Debian, between a user wanting a stable system, but with the latest and greatest desktop software. Even with an army of volunteers, Debian still tends to release stable OSes every couple of years, with userspace software that, for the most part, maintains a similar vintage. This has discouraged innovation in desktop software, as developers who want to write software for the Linux desktop have to care about the differences between Debian, Arch, Ubuntu, Red Hat and others, and hope their software is popular enough that a volunteer will maintain its packages for that distro.

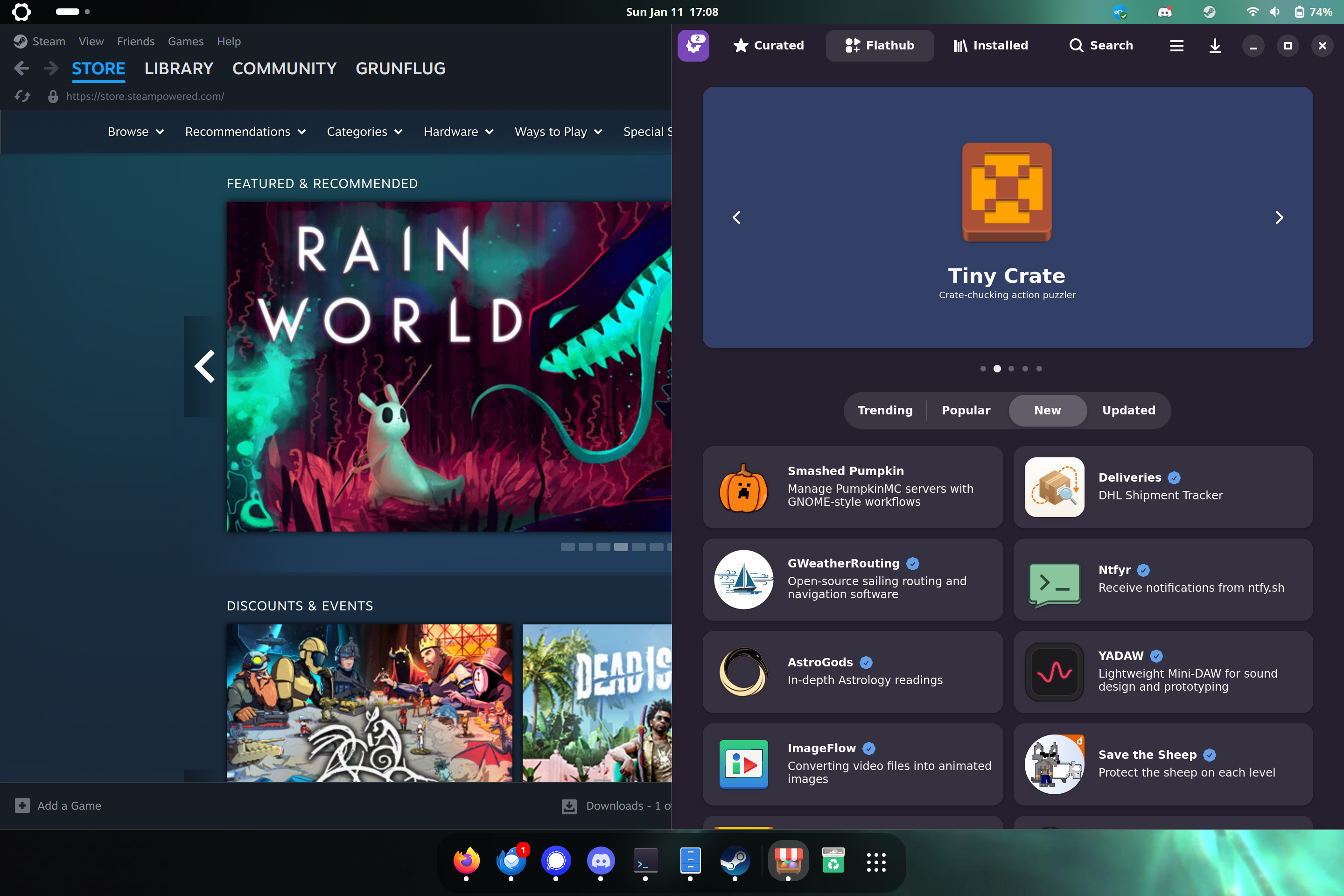

One of the main solutions to this dilemma is to ship desktop software in containers just like in the cloud. Disk space is no longer at the kind of premium we had in the days where shared system libraries were critical, and container technologies take advantage of similar base images to provide some level of space savings anyway. Technologies like Flatpak make it possible for a developer to build their software in a Flatpak container once, and have it work on a wide range of Linux desktops regardless of whether that distribution's system libraries might differ from their software.

The adoption of Flatpak with Flathub as a central, distro-agnostic, repository for this software, has spawned a new and exciting era of Linux desktop apps. This mirrors the growth we see in mobile app stores, because developers are finding it much easier to create and ship software for Linux when they don't have to rely on distros as a middleman. Like with containers in the cloud, the distro a Flatpak ends up on largely no longer matters. In fact, a distribution that packages your software in their own package format is more a problem than a help, as that middleman may not ship your most up to date software, leading to bug reports from your users you have already addressed, but can't fix for their platform.

Images on the Desktop

In addition to containers for userspace applications, the desktop Renaissance is marked by an innovation in how the system itself is created. Image-based atomic systems using technologies like OStree and bootc, and demonstrated in projects like Fedora Silverblue and platforms like Universal Blue provide stability in the sense that every user is running from the exact same image. Any bugs you hit are hit by everyone, and resolving regressions can be as simple as moving to the previous image. Combined with Flatpaks, you can run the most up-to-date version of userspace software a developer has created, without worrying that it will interfere with the stability of the rest of the system.

While Flatpaks address desktop GUI applications, that still leaves the question of how to manage command line software. This is where Homebrew for Linux comes in. This same system that provided command line software for MacOS is just as capable on Linux and has become a go-to supplement for Flatpak on image-based systems that don't want the burden of maintaining builds for all of these command line tools.

The Year of Gaming on the Desktop

A final innovation that has led to new interest and adoption of the Linux desktop has come from an unlikely place: gaming. Valve's investment in the Steam ecosystem on Linux, in particular Proton--Valve's project to allow the Linux Steam client to run Windows games on Linux--combined with SteamOS and devices like the Steam Deck has seen Linux unseat Windows as the premier gaming platform. A whole new generation of users are trying Linux for the first time, because it is offering them the best gaming experience.

These new users are coming to Linux with few preconceived notions for how Linux should be, no particular awareness or loyalty for how things were done historically, and aren't motivated by Open Source ideology. Instead they are looking for a polished and performant gaming experience. While these users may not be familiar with Linux, they often bring a lot of technical knowledge, especially about graphical hardware, and are willing to tweak and tune things if necessary to get the best performance out of their hardware--something Linux has long encouraged. This is exactly the kind of user you would want if you want to shake off inertia, experiment with new ideas and bring fresh perspectives and energy into a stale platform.

One of the best examples of a confluence of all of these Renaissance traits can be found in Bazzite. Bazzite is a gaming-focused Linux platform based on Universal Blue similar to Bluefin (a next-generation Linux desktop platform built on cloud native technologies). In particular Bazzite showcases a Linux desktop with a SteamOS-like experience, but based on the cloud native technologies that are the hallmark of this desktop Renaissance. This provides that critical balance between a stable but up-to-date base system, with the latest and greatest Linux desktop software.

Personal Experience

I have been using Bluefin as my personal desktop for a few years now, and it's amazing to have a combination of a stable system while also being able to enjoy the latest and greatest desktop software Linux has to offer. There truly is an amazing set of next-generation desktop software being developed on Flathub right now, and it's nice to try it out without having to worry about compatibility, or whether it might break some other part of my system. I say without reservation that if you want the absolute best Linux desktop experience right now, especially if you are used to the polish of a Mac, it's a combination of a Framework 13 AMD edition with the 2.8k screen, running Bluefin (or Bluefin-dx if you are a developer).

I use automatic updates on this laptop (the default), which means I get the latest OS updates and latest userspace software all in the background. Every now and then I might reboot my system to ensure I'm on the latest kernel but that's about it as far as maintenance goes. I no longer have the worry that some OS update is going to result in a few hours of troubleshooting.

It's true that when I get under the hood, that Bluefin does things differently from a traditional distro. Tweaking and tuning might (gasp) mean learning new things, and possibly using new tools. Fortunately for me, I was never one of those Linux sysadmin who climbs their initial learning curve, and then stops wanting to learn new things once they hit a senior level. Instead I've always enjoyed that technology is constantly moving because I actually like learning new things. I view my experience living through many boom and bust cycles as a tool to see through what's hype and what's useful, and weigh the promise of a new approach against the value of a proven, historical approach.

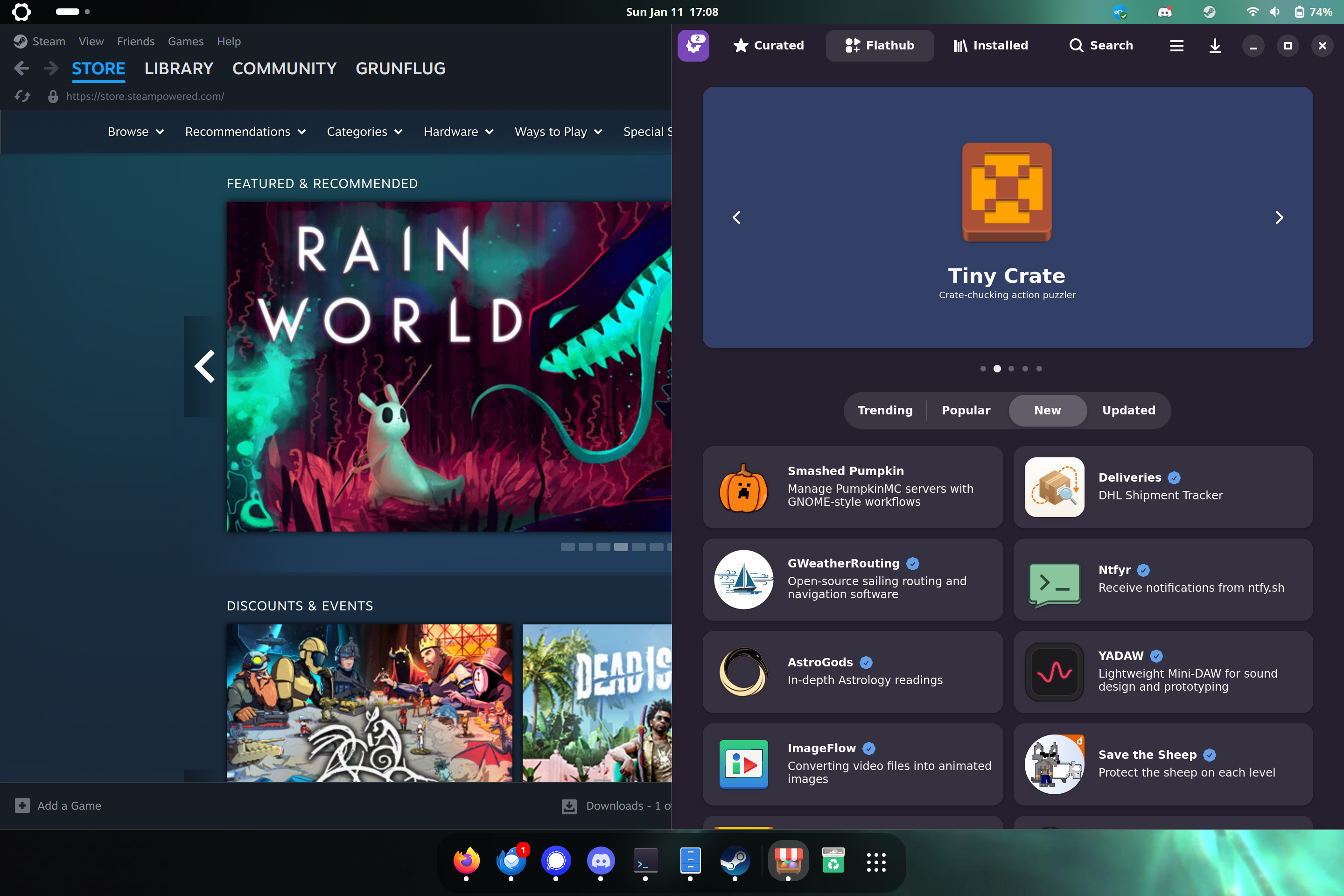

A screenshot from my current Bluefin desktop

What's Next

I think what's most exciting about the desktop Renaissance is the rapid innovation with relatively small teams that the adoption of cloud native technologies has allowed. There is a lot of momentum being built inside this wave and if the past five years are any indication, the next five years are going to be very exciting. Here are a few things to look out for.

Cutting out Middlemen

I think the next few years will see the Linux community focus on more direct relationships with software developers, and a fresh look on whether all of current middlemen that sit between software developers and users are still needed, given some of the modern tools we have compared to three decades ago. It's a good time to have this conversation, because the Linux community has been around long enough that we are starting to see some of the early contributors retire, or get burnt out by the burden of maintaining an always-growing set of packages.

Flathub will likely become the default source people turn to for graphical software, with distribution packages for the same software becoming less relevant. It's easier for the developer than supporting multiple distros, and provides a more controlled, predictable environment for their software, which eases debugging while also allowing users to add tighter security controls on those containers. New software is showing up on Flathub all the time, and users won't want to wait for their distro to get around to packaging it, when they can get it from Flathub.

Homebrew will likely provide a similar platform for non-graphical tools in much the same way it has done for MacOS for twenty years. There are a lot of modern command line tools out there that make your shell environment much nicer to work in, and I see Homebrew as an ideal platform to bubble some of the best to the top.

So where does that leave traditional package managers? The main remaining use case is supporting system software for traditional distributions, as container-based workflows both in userspace and at the system level with bootc often find you layering images on top of each other. While in some cases the build scripts behind these layers deploy traditional packages, that's not a necessity.

"Distroless" Linux

One of the interesting experiments currently going on within Bluefin is around building a Linux platform that isn't based on any particular Linux distribution for its foundation. Instead, the initial bootc containers provide a kernel and enough of a foundation to host the desktop environment (Gnome in this case).

The question of course is where distributions and their communities fit in to this "distroless" future? I don't have good answers myself, but my hope is that some of those resources get redirected into common sets of tools that are useful regardless of what Linux platform you install. I suspect there will still be a place for platforms that focus on particular use cases like software development, gaming, and security. The overhead of maintaining these platforms will ultimately be much lower, at least if the platforms are building on some of the technologies behind this Renaissance.

User-controlled "AI"

While there is plenty of hype around LLMs (Large Language Models), there are also some interesting use cases coming out of open source models that can run locally. Tools that use both remote and local models are being developed at an incredibly rapid pace on Linux. The pace is so rapid that it's hard to say what things will look like when the dust settles, but we are already seeing some standardization being promoted within the Linux Foundation.

I have plenty of qualms with the current hype around "AI" but I also think there is potential behind locally-run, Open Source models that are fully under the user's control (and consent). I've written a lot of things over the years, and while I wouldn't use AI for my writing, I think it would be pretty handy to have a locally-run "librarian" assistant that was familiar with everything I've ever written, and could work as an extension of my memory.

In any case, this is a space to watch. The Renaissance Linux desktop could become the ideal development platform for innovation in locally-run, Open Source AI tools after the current AI boom turns to bust.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Back to Index